LAYERS

Cantina, Århus, Denmark, 2025.

Installationsview, Layers, Cantina, 2025.

(1 / 8)

LAYERS

Cantina, Århus, Denmark, 2025.

Notes on Layers.

“Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” [1]

The career of Swedish architect Sigurd Lewerentz (1885-1975) had three phases. The first and last of these periods of activity, which produced his most celebrated buildings, seem in some sense at odds with the middle part of his career. Put simply, the middle phase (1930 – 1955), marked as it was by the founding of Idesta, a company manufacturing high quality retail and display systems (shop windows, doors and vitrines), seems preoccupied with the most superficial aspects of modern urban life, with commerce and display, while the beginning and end of his career are best known for his work on a number of extraordinary projects that engage with the most fundamental of existential questions – with life and death and the journey of the eternal soul. These early and late masterpieces include the Woodlands Cemetery (1920) and St. Mark’s Church (1956), both in the Stockholm suburbs, and St Peter’s Church (1963-1966) at Klippan, Skåne.

As a building for the propagation, display and sale of flowers to visitors to Malmö’s Eastern Cemetery, the Flower Kiosk (1969)[2], designed when Lewerentz was 84 years old, appears to connect his involvement with retail architecture and his work on those more profound, more existential projects. With its elegantly elongated, south facing, shop-front glazing showcasing the Kiosk’s wares, and its two, north facing, elevated ‘eyes-to-the-sky’ windows, bringing much needed light to the plants housed inside, this ostensibly brutalist, twin-faced building can be understood as a bridge between the different phases of his career, between the superficial and the fundamental, the commercial and the spiritual. The Flower Kiosk is a retail space which, through its carefully executed simplicity, its insistent materiality, its soaring Verdigris roof and its Janus nature, is capable of evoking powerful emotions, channelling thoughts of life, death and renewal.

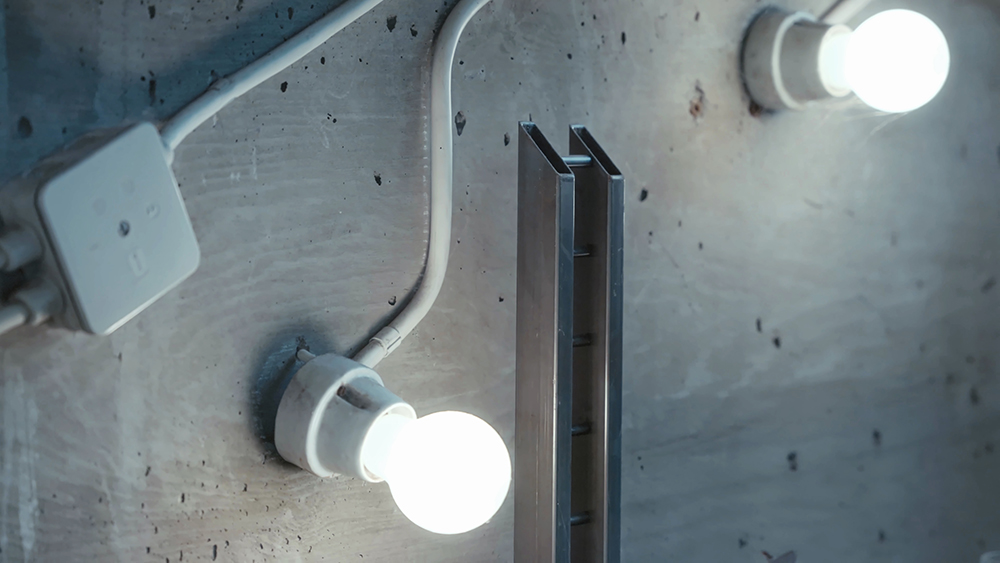

In Jonas Handskemager’s short film Layers (2025), we enter the Flower Kiosk, like the northern light, through one of the two high square windows – an elegant, flush-fitting, interface between inside and outside – a surface on which the characteristic silver foil ceiling cladding [3] (inside) and reflections of the surrounding winter branches (outside) coalesce, skin-like. The camera’s restless eye, pulls us inside, floating amongst the light fittings. Nothing functional is hidden. We track Lewerentz’s ivy-like electrical wiring that creeps rhythmically along the raw concrete walls – junction box downbeats, light-bulb backbeats. A xylophone accompanies our swirling trajectory, speculative, fairground-like. We are immersed in vegetation, both for the living and the dead, potted plants and cut flowers, deeply veined philodendron leaves, vibrant winterberries, peonies, dahlias, carnations and white lilies. A figure lurks, ill defined. The sound of a machine draws us in.

In this dualistic scenography of concrete and flowers, the anonymous protagonist, a densely tattooed, heavily muscled man, seems incongruous at first, anachronistic even. A fish out of water. But his skin, taut over well-schooled muscle mass and prominent veins, is covered in filigree inked ornamentation, flora and fauna, a skull, a lotus flower, a butterfly, tangled vegetation, all muted in the Flower Kiosk’s soft winter light, but resonant here, nonetheless. He seems to be engaged in a quasi-ritualistic, bodybuilder’s warm-down – his carefully choreographed movements are a self-taught duet for man and machine.[4] He presses the gently vibrating cushioned pad of what appears to be a generic car polishing machine against his chest and arms, massaging inflamed muscles, soothing the microtraumas so vital to his body’s transformation. [5] The polishing machine, like the camera that tracks it, was built with surface concerns in mind, the external shell, the play of light, but here it has been repurposed for internal affects – to go deep. In Layers, it seems, we occupy a liminal space in which binary ideas of inside and outside, the building and the body, ornament and fundament, are constantly upended and destabilised.

Finally, the restive camera swirls away again, more plants, that rhythmic wiring, another filigree forearm and then a bow of sorts – his mechanical dance partner laid to rest. We leave, as we arrived, through glass, markedly more skin-like than before, and then out into the winter gloom of the late afternoon.

Simon Starling, visual artist

The exhibition is supported by Aarhus Kommune.

- [1]This quote has been variously misattributed to musicians Laurie Anderson and Elvis Costello. Costello himself has attributed the quote to the comedian Martin Mull but a variation (“talking about music is like singing about economics”) has appeared in print since as early as 1918.

- [2]Jonas Handskemager’s first work connected to Sigurd Lewerentz’s building “Untitled (Flower Kiosk), 2022, a somewhat austere black and white photograph of the Kiosk’s north façade, seems in retrospect to be a prelude to Layers. The image transforms the building into scenography – a cobbled stage with a concrete and glass theatrical flat behind.

- [3]It is perhaps interesting to note that Lewerentz’s final architectural practice was operated out of a studio in his back garden known as the Black Box. Designed for him by fellow architect Klas Anselm while Lewerentz was working on the Flower Kiosk project, this tarpaper-clad structure with its three modest skylights is noted for its Warholesque reflective silver foil wallcovering, the same material that bounces the sometimes-scarce Malmö sunlight around the Flower Kiosk. Andy Warhol’s quintessentially pop decoration for his New York studio, installed in 1964, was inspired by the apartment of photographer, filmmaker and lighting designer Billy Name. The look and feel of Lewerentz’s studio link it to another black box, the world’s first film studio, Thomas Edison’s similarly tarpapered Black Maria (1893), in which Edison made a number of early film experiments, the first of which was a short film of three actors playing blacksmiths working at an anvil. Unlike the skylights in Lewerentz’s studio, the Black Maria had a whole section of roof (reminiscent of the sloping roof of the Flower Kiosk) that opened up to allow light into the studio for filming.

- [4]Accompanying Layers is a photographic work Well it doesn’t see you (Maison de Verre) (2022) glazed beneath a so called ‘privacy screen’ developed for mobile phones and computers. Viewing the image demands a certain dance of our own – a side-stepping jig from the visible to the invisible and back again. The image, that comes and goes depending on your point of view, sometimes engulfed in blackness, sometimes crystal clear, is of an enduringly radical Parisian house, the Glass House (1928 – 1932) designed by architects Pierre Chareau, Bernard Bijvoet and blacksmith Louis Dalbet and best known for its façade of translucent glass bricks. “During the day, the sunlight filters through the glass blocks, casting an ethereal glow across the house. At night, the house becomes a luminous beacon, with light radiating from its glass façade (…) a clever interplay between the visible and the hidden, the public and the private.” (Archeyes.com))

- [5]“You’re part of a choreography that the architecture is a background for. The body itself goes in as one thing and leaves as another” (Sven Blume, Lewerentz, Divine Darkness, 2024)

WHAT DO YOU WANT

Bladr, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024.

Installationsview, WHAT DO YOU WANT, Bladr, 2024.

(1 / 7)

WHAT DO YOU WANT

Bladr, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024.

There are the things we can’t have. The sold-out things and the expensive things and the invaluable things and the things that just aren’t for sale. Essentially, these categories don’t include a lot of things. We have so much money, at least those of us who are able to choose what we want. Something shiny, something temptingly rounded, something soft-looking, something weighty and well-crafted. Quality. What did that term even mean prior to nonstop materialism. What did nonstop materialism even mean prior to photographs.

A camera can provide images of beautiful things (and all sorts of other things, but isn’t most desire directed at beauty and aren’t most photographs motivated by desire). Craving silk or whatever is gilded or some terrific weapons or just a gorgeous little vase rose comb kitten glove. This is naturally a timeless feeling, but it seems reasonable to think that there is a substantial difference between wanting things from your more or less immediate visual field and wanting things from the cornucopia-like scope of photographed imagery. That the emergence of photography might literally have made us drool more. That actual wanting might be purer when the feeling sprouts from being in the physical presence of what you want.

Imagine what desire was before the camera, imagine what it entailed to want something before the age of mechanical reproduction. How the wanting possibly manifested itself in quite various manners. Having to lay your actual eyes on something in order for the possession-sparked fire to start burning versus lying in the all-seing privacy of your screens, yearning for new heels or new partners. Things containing the dubious promise of making life sexier, a bit more joyful.

It might be the thing itself, but how would we know about the urgent need for that particular aluminum surface if it wasn’t for the representation of it. Let’s say that the thing is bound to disappoint. A rush of pleasure, sometimes lengthy and deep, will of course usually occur when we get what we want. The monumental delight in a flawless accessory or sudden erotic epiphanies is real. But then something breaks, corrodes, gets habitual or ultimately useless. Do we want things more if we can use them.

Upon landing in the center of a London fashion crowd in the early 1970s, Manolo Blahnik quickly became acquainted with an A-list of influential people, publishers and shoe wearers alike. Who makes us want what we want. When things become older and rarer, new intensities of desire begin to occur. Reselling, online auctioning, ways of presenting collector’s items in order to make them look sensational.

A shoe horn, images of a shoe horn, a sculpture, functionless works of art. You can have it all.

Nanna Friis, art critic

The exhibition is kindly supported by The Danish Arts Foundation, Danish Art Workshops and City of Copenhagen Visual Arts Council

HANDLE, HANDLES

Heerz Tooya, Veliko Tarnavo, Bulgaria, 2024.

Installationsview, Handle, Handles, Heerz Tooya, 2024.

(1 / 7)

HANDLE, HANDLES

Heerz Tooya, Veliko Tarnavo, Bulgaria, 2024.

With his latest photo series, Jonas Handskemager invites us to explore how photography shapes and mirrors our perceptions in today’s society as it increasingly becomes a commodity in our visual culture. The series features Polaroids of a door handle designed by the acclaimed Danish architect Vilhelm Lauritzen. The door handle essentially introverts these Polaroid’s mechanical development as means without human intervention, thus functioning as a conceptual and linguistic tool that interjects itself between our emotional connection to images and the symbolic meanings they might convey.

Amidst the winds of change and shifting paradigms, we strive to capture and frame these transformations. Yet, in our pursuit, we often inadvertently filter out the very essence of change itself. This exhibition invites us to ponder: are we still in the crisis of the aura, or does the aura still playfully tease us, reveling in our awareness of its crisis? Viewing and presenting photography, as mucht as capturing it, not only immerses us in the complexity of value but also raises the crucial question of how we interact with and handle it.

Lars Nordby, artist/curator

The exhibition is kindly supported by The Danish Art Foundation.

I SIMPLY AM NOT THERE

Danske Grafikere, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024.

Installationsview, I simply am not there, Danske Grafikere, 2024.

(1 / 7)

I SIMPLY AM NOT THERE

Danske Grafikere, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024.

If the pots by Italian architect Aldo Rossi (1932-1993) – the coffee pot La Conica and the tea kettle Il Conico designed for Alessi in 1983 and 1986 respectively – had been part of the inventory of Patrick Bateman’s apartment in American Psycho (1991), we would have known. The narrator and main character in Bret Easton Ellis’s novel happily and consistently lists everything he surrounds himself with, owns and uses, sometimes repeatedly. For example, we are told on both pages 62 and 64 that the shoes he is wearing are crocodile skin loafers made by A. Testoni. Bateman appears to be an influencer before social media existed: he gives tips and advertises exclusive brands as he goes about his morning routine – not to earn money from sponsors, but to ‘show the money’, as it manifests on his body, in his home and around the people he associates with.

American Psycho is a catalogue of the brands and designs anyone who would want to venture into the yuppie milieu of 1980’s New York should know. But the book is also a reflection of its protagonists’ materialism- obsessed as they are with flashing their style and their knowledge of it, painting a picture of “the ennui of morally bankrupt extreme privilege.”[1] In the conversations between Bateman and his colleagues, women are also reduced to brands that denote where they come from and what type of value they reflect: Vassar / Camden / Queens ... Among the book’s protagonists, there is a constant exchange of objects, locations and people (for Bateman there are always new clothing brands to desire, a new place to eat, a new woman to date or kill, movies to rent and clothes to pick up or drop off). Desire lies in the pursuit of the next and newest item – a version of an accelerated consumer culture on coke.

It’s no surprise that the book and film became huge, albeit controversial, successes. The book, with its narrative style and detailed descriptions of characters’ appearances, details of the different spaces in which action takes place, and not least Bateman’s violent behaviour, already has a strong cinematic quality. Patrick Bateman tells his story as if it were a movie with “smash cuts,” “jump zooms,” and “pans” and detailed descriptions of his emotional reactions to the action that is unfolding around him – jealousy, clenched fists, and other physiological reactions. As readers, we are invited to see the world through Bateman’s eyes, but he himself is not there. He is pure projection, imagination, mirroring:

…there is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory,and though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable: I simply am not there. (American Psycho, p.794)

Therefore, it seems only fair to introduce Rossi’s stainless steel pots, so shiny that you can see your own reflection in them, in the middle of Bateman’s universe. Through a series of digitally rendered images that Jonas Handskemager has animated for the exhibition ‘I simply am not there’, we are confronted with this imaginary encounter. Here, the two design icons are placed in the middle of the glass table in Bateman’s living room. There might be a slight hesitation here before realising that the image is not a still from the film or a photograph of the film’s scenography. In the animations, the apartment reflects itself; the surfaces of the pots reflect spots on the ceiling and the glass tabletop mirrors the pots. The apartment is an empty place, an open place, a place that exists only in the space of the animation, fantasy or the imagination. The intervention in the narrative and its visual world continues Bateman’s preoccupation with smooth, shiny surfaces of steel, glass, marble and silver, such as the kitchen, in which “large glass-front cabinets ... make up most of an entire wall ... complete with stainless-steel shelves and sandblasted wire glass, it is framed in a metallic dark gray-blue.” (American Psycho, p.61). The reflecting surfaces of the animated objects reflect the self-absorption of the narcissist, where everything revolves around the individual in question. In Bateman’s own words: “Since it’s impossible in the world we live in to empathise with others, we can always empathise with ourselves.” (American Psycho, p.539).

Just as Bateman surrounds himself with design icons, through the reception of the book and the film, he himself has become a condensed image of a superficial, materialistic, narcissistic culture. At its most extreme this culture has manifested Bateman – a beautiful, articulate and lean psychopath who hides his murderous tendencies beneath a charismatic facade. If Aldo Rossi’s kettle and coffee pot had been part of Bateman’s household, they may have been the focal point of a breakfast or murder scene, depending on the main character’s mood: “Patricia will stay alive, and this victory requires no skill, no leaps of the imagination, no ingenuity on anyone’s part. This is simply how the world, my world, moves.” (American Psycho, p.165). This reinterpretation of the objects’ function both resonates and contrasts with Rossi’s position as a designer.

Rossi was preoccupied with accumulating forms and employing them in new contexts and with new functions, just as he was interested in the meeting between architecture and design and the individual and collective memories associated with them. Rossi’s postmodernism is characterised by the use of quotations, reinterpretations and repetition: “in my projects, repetition, collage, the displacement of an element from one design to another, always places me before another potential project which I would like to do but which is also a memory of some other thing.” (Rossi , A Scientific Autobiography, p.20)

In Handskemager’s exhibition, the displacement of both objects and cinematic space, which takes place through digitally rendered images, gives occasion to consider the glossy and smooth as characteristic of American Psycho and it’s main character. The subtle displacement and amplification of the book’s style clarifies a point about consumer fetishism: to attach a promise of satisfaction to a fetishised object, one fixates its qualities so that it cannot move, shift, or respond; it becomes an object which does not exist outside the subject’s imagination.

At the same time, the use of quotation in Handskemager’s works punctuates this fixing fetishism and serves rather as an example of the possibility of reinterpreting objects and environments alike. This artistic strategy points to a shift in meaning of objects and environments depending on the context they are placed in. In Rossi’s own words – “(t)he emergence of relations among things, more than the things themselves, always gives rise to new meanings.” (Aldo Rossi, p.19). The presence of Rossi’s pots in Bateman’s apartment echoes another image from Handskemager’s exhibition which is a photograph from Rossi’s personal archive – a snapshot of his coffee pot La Copula, which he himself is reflected in as he photographed it. There is a tendency to read Bateman’s psychopathology as a result of the consumer culture he is a part of, but if we turn the fiction on it’s head once more and imagine Aldo Rossi lived in Bateman’s apartment, surrounded by his belongings, what would have happened? We can imagine that things were sent into circulation – not to kill, but to create new objects and forms. Rossi would probably have turned the apartment into an inhabited place; with freshly brewed coffee.

Text Anne Kølbæk Iversen, PhD, researcher, curator, editor, and writer

Proofreading Sam Derounian

The exhibition is kindly supported by The Danish Art Foundation and City of Copenhagen Visual Arts Council

Thanks to: warrenn81, Sidse Thorup Poulsen, Ebbe Stub Wittrup

- [1]Irvine Welsh, “American Psycho is a modern classic”, The Guardian, 10. jan. 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jan/10/american-psycho-bret-easton-ellis-irvine-welsh

STUDY OF PLANTS AND MUSIC

Public commission w. Ebbe Stub Wittrup, The Radiohouse, Copenhagen, 2023.

The Study of plants and music, documentation film, 2023.

(1 / 1)

STUDY OF PLANTS AND MUSIC

Public commission w. Ebbe Stub Wittrup, The Radiohouse, Copenhagen, 2023.

The roof is green. It was covered in earth so plants could take root and sprout there, and so the roof can burst into bloom every time a new spring arrives. Nature stands on top of music, as though notes were also the roots and the fertilizer of this little forest. A piece of landscape that grows and blossoms and wither alongside symphonies beneath it. A tree with cello or brass sounds in its trunk.

Is peace more distinct, does it get a more tangible body in the context of what we consider nature, or is this merely something we have agreed upon because landscapes are silent. Because landscapes are the opposite of a house. Long before music there were plants, and long after humans, the notes they composed will be audible: there must be different eternities, one of the Earth, one of the arts. And here is a moment: an architectural moment and a musical moment and a biological moment where everything exists side by side, giving something to the others and taking something from the others.

Jonas Handskemager and Ebbe Stub Wittrup have scattered 4 loudspeakers across the roof of The Radio House in Copenhagen, sown them like seeds in the rooftop garden which was a pioneering architectural decision, when Vilhelm Lauritzen took it in the 1930s. It is a rather secret garden, squeezed between windows and stairscases to provide rehearsing musicians with the possibility of drawing the most sprouting breath possible. Take their tranquil breaks. And now the newly sown loudspeakers will make the garden melodic, they’re connected to rooms below the organic roof where music takes shape and is being refined. Rehearsing clarinets or violins stream into the garden, music itself ascends through the root system in order to properly inhabit nature. Never will orchestras make gardens bloom, but that plants too are alive and can soak in symphonic beauty, this is something we know. That human hearts and states of minds, that also leaves and flowering and deflowering, can be nurtured and tended with the emotional infinity of music, this is something we know.

Next to the sounds: the gaze. Just as the house and its sounds is drawn up into the garden and the air, the sky is drawn down into the house. 8 round windows in the Radio House ceiling – yet another architectural vision about having inside and outside meet – have had their panes replaced with camera obscura lenses. And so, the world is mirrored and poured into whichever open eyes that would be standing in the middle of a regular day, in the middle of a regular corridor, looking up. The garden and the clouds and the peculiarities of any regular day are turned upside down and brought inside, down through these light pits in the roof, down through the enigma that a camera obscura is. A beautiful or un-beautiful reality is simultaneously transmitted and splintered in the lenses, the world probably always looks like the mood of the eyes, but inversions of familiar moons and birches above us cultivate the imagination. Keep looking and listening.

A study of plants of music is an attempt at approaching and contributing to the synthesis that Vilhelm Lauritzen established eight decades ago: inside the house are melodies, a sun or a darkness, alternating skies, green life, human life and art, and on top of the house are melodies, a sun or a darkness, alternating skies, green life, human life and art.

Nanna Friis, art critic

Film production crew

Director Émile Sadria

Producer Émile Sadria

Director of Photography Troels Rasmus Jensen

Editors Jesper Fabricius, Oliver Hyttel Reddersen

Sound Ludvig Jakob Trier

Voice over text by Nanna Friis

Voice over artist Janus Kodal

Colourist Olesya Kireeva

Colourgrade Storyline

Production Delta Productions

The project is supported by Danish Art Foundation, Danish Art Workshops

Thanks to: The Royal Danish Academy of Music, Storyline, Delta Productions, Augusta Møllemand Jensen, Vilhelm Lauritzen Architects

CV

Jonas Handskemager (b. 1987) is a visual artist based in Copenhagen.

EDUCATIONS

Fatamorgana, The Danish School of Art Photography, Copenhagen

SOLO SHOWS (SELECTED)

Layers, Cantina, Århus

WHAT DO YOU WANT, Bladr, Copenhagen

Handle, handles, Heerz Tooya, Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria

I Simply Am Not There, Danske Grafikers Hus, Copenhagen

GROUP SHOWS (SELECTED)

S2E2, Portland, Zürich

A Study Of Plants And Music,The Radiohouse, Copenhagen (public commission, w. Ebbe Stub Wittrup)

Bedrock 2, Ladder Space, Copenhagen

GÅ, Kunsthal Sophienholm, Kgs. Lyngby

Afgang2020, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen

det 2. Bud RW + 19, Richard Winthers Hus, Vindeby, Lolland

Saint Antonios Fristelser, Galleri Tom Christoffersen, Copenhagen

Courage Afternoon, Sydhavn Station, Copenhagen

Overgang – Hyper, Museum Ovartaci, Risskov

Buds Are Breaking, Bådehavnsgade 42, Copenhagen